From the Heart: Our Vision Mission

- Avinash Jayaraman

- Jul 1, 2014

- 7 min read

Updated: Jun 4, 2024

An article by TVM Founder Avinash Jayaraman on the Singapore Medical Association's monthly newsletter

The word tribal conjures up images of a merrily oblivious forest dweller skipping along in sunny idleness in comedy film The Gods Must Be Crazy, or a content hamlet in a television documentary. But the reality one experiences in the tribal heartlands of India is much removed from this picture, and so is the tragedy. The tragedy is not one of Dionysian isolation. It is of people living with the least medical care despite being in the centre of bustling and moving civilisation; of not being able to benefit from what modern sciences have to offer for healthcare, while steadily losing knowledge of traditional herbal remedies built over millennia; of a people being able to neither live a hunter-gatherer life nor join the mainstream economy. In Odisha, a state on the eastern seaboard of India, between the bisections of large national highways, a massive human-built reservoir from the Hirakud Dam, a rusticyet-bustling area of commerce, is a populace stuck in limbo between several centuries. 22% of the population is tribal (or officially termed “scheduled tribes”). Meanwhile, the scheduled castes, people similarly backward and unfortunate for hundreds of years, bring up the rearguard of the state. Being the only non-doctor among a triumvirate of us who visited the region in February this year, I am writing this article essentially for a non-medical audience like myself. Back in the middle of last year, my close friend (and ophthalmologist) Dr Jayant V Iyer approached me with the idea of starting a social enterprise aimed solely at eradication of curable blindness. He and a fellow eye doctor, Dr Jason Lee, had volunteered at several eye camps in developing countries and performed cataract surgeries for the poorest there.

Dr Jayant’s idea was to build a non-profit entity that would work towards providing basic eye care to all who need it. While there are several charitable organisations working towards providing better healthcare, only a few are exclusively devoted to improving vision. Furthermore, the two doctors felt that it would be good to have a group acting as a conduit between ophthalmologists in Singapore who wish to contribute and serve such communities, and developing countries or regions with a sore need for such expertise. With these objectives in mind, we started The Vision Mission in Singapore in December 2013. We identified areas in war-ravaged northern Sri Lanka, Myanmar and eastern India that have a huge demand for such services. By the new year, we had worked out a plan for a five-day camp in the Indian state of Odisha, in partnership with a wonderful team based there. We had initially planned and raised funds to conduct 150 free cataract surgeries at three locations in Odisha – two in the district of Sambalpur, and one in the district of Kalahandi. Our primary concern was the publicity for the camps – would sufficient people show up at the assigned dates and locations to receive treatment? For this, we were dependent on our local partner – another young but very determined organisation called Trilochan Netralaya (TN). Its visionary founder, Dr Shiva Prasad Sahoo has worked tirelessly and selflessly over the years, trying to eradicate curable blindness in the region. Dr Shiva has performed over 35,000 cataract surgeries in his career – a staggering number by any standard. He also has a team of equally dedicated staff at his establishment who match his diligence and sense of duty.

Restoring sight to the poor On 8 February this year, we flew to Kolkata (formerly Calcutta), where we spent the night, and devoted a good portion of the following day to wandering the city’s streets. We visited the imposing Victoria Memorial built when Kolkata was the capital of British India. The lone Chinese guy in our midst swore off meat for the week (mainly because we scared him on this account) and professed to be vegetarian like the other two of us. In the late evening, we took a train from Howrah Station to the district of Sambalpur. During the journey, the two doctors tried their best to give me a crash course in Ophthalmology, so I could have a better appreciation of what would be involved in treating the patients, apart from carrying out my tasks of documenting, videographing and photographing the camps. Alas, I am unable to comment on their success. We reached Sambalpur in the early morning of 10 February. Upon landing, we freshened up and proceeded to the first camp, which was located within the township of Sambalpur. What we didn’t expect was the embarrassingly warm and elaborate reception that awaited the three of us. A big poster at the entrance screamed our names and a very traditional Indian welcome (including petal showering, flower garlands, and lamp lighting) made us wonder if they had mistaken us for movie stars or visiting dignitaries.

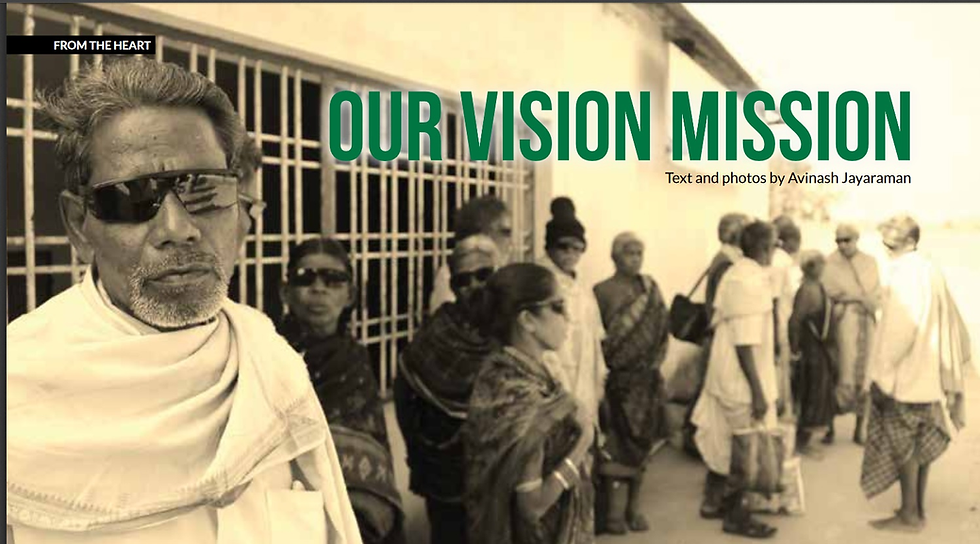

We exchanged curious and flummoxed glances at each other for we were neither; just a trio of below average-looking men with slightly pachydermous bellies, no achievement to our name, save for the fact that we had come up with the idea of making this trip over tea at a small stall in Hill Street. Protocols completed, Dr Shiva made a small presentation on the nature and state of eye-care in Odisha. There are close to a million people suffering from cataract in the state, and a couple of hundred thousand is added to that list annually. But the supply of surgeries – both paid and free – are well below that number. Our initiative, in this regard, seemed like a drop in an ocean, and redoubled our urge to do more. I started calling our donors in Singapore to try and see if we could raise more funds by the end of the week. We felt confident that we would breach the initial number of 150 surgeries within the first two or three days. While I got busy on the phone, the doctors got busy with what they did best. Dr Shiva also asked them to provide a second opinion for the more unique cases. We also spent some time conducting surgeries at TN’s more remote site – a rustic, countryside facility, called Betty’s Ashram, named after the very generous donor who funded the building. On the third day, we left by road, moving further into hinterland for Bhawanipatna, a town in the Kalahandi district. The internal districts are also infamous for armed conflicts and rebellions by groups known as the Maoists. Our hosts reassured us that medical workers did not have a reason to be worried as they were never harmed. Even though it was mostly dark, the drive – through river beds and dense woods – was a beautiful one. We got the opportunity to have some interesting conversations with Dr Shiva and find out what inspired him to immerse himself in social service. Dr Shiva himself was the product of the largesse of others – both governmental and non-governmental. As he explained, “I was born in a very poor background, but got to study through school and college for free thanks to various donors.” He subsequently resolved that it was then his turn to give back to society for what he had received from it. We eventually had a fruitful time in Kalahandi as well, carrying out almost 80 surgeries. Needless to say, TN had done a fabulous job with the evangelism of our three camps. Large numbers of people had gathered at each one. A majority were old and frail, and obviously could not afford even the most basic medical care, evident in very visible symptoms. Even an untrained eye like mine could make out the wide patches of cataract from a distance. (I was even able to see the various rashes on feet and limbs, emaciated frames and bent backs.) In the developed world and the more affluent sections of the developing world, people would undergo surgery to correct cataract at the very incidence of symptoms. You would not see a patient with a white patch that wide in his eye. This observation was something that both doctors concurred with. Most of the patients had been ferried in by road from villages in a radius of about a hundred kilometres. These were people who are too poor to even be able to afford the bus fares for the trip. A lot of them had little or no idea of their ailments, or even what the actual procedures they would be undergoing were. Therefore, trained local assistants were needed to take them through every step of the process. The camps also included facilities to house the patients, cook and provide food for them over a day and a half, while they rested and recuperated. In all, a total of 300 free cataract operations were performed – double that originally planned. Our pledge included the costs of bringing patients in, intraocular lenses, accommodation, food, and post-operative care for them. Luckily, we were by then, successful in raising more money from our very kind donors to support the higher number of surgeries. We would like to sincerely thank them, as the credit of 300 people regaining their sight is mostly theirs. The three of us merely played the part of custodians to their nobility. A supremely humbling experience During our five days in Odisha, although our ability to directly communicate with patients was impeded linguistically (the locals spoke a specific dialect of one of India’s many languages), we still managed to sense the high esteem the poor patients held the doctors and nursing staff in. There, the doctors were treated with a combination of admiration, respect and love.

The Vision Mission team was very inspired by Dr Shiva and his team of dedicated staff. Dr Jayant and Dr Lee were also very impressed and humbled by the high level of skill that Dr Shiva displayed in managing complicated cataracts. What is needed now is backing in the form of correct training, mentoring and funding so that TN can provide holistic high-quality ophthalmic care beyond just cataracts. It goes without saying that much more can be accomplished in future mission trips in the form of training the staff, and augmenting their skillsets. It did get us thinking that the setting up of some form of telemedicine facility in those areas could greatly enhance the quality of service. It was a splendid week and a great learning opportunity, and most of all – a supremely humbling experience for the three of us. These 300 are just the beginning. We intend to continue supporting Dr Shiva and his fantastic team in greater ways, with the help of more donors, volunteer doctors and experts. We wish to hopefully commit to more surgeries for the year ahead, and beyond, and are also excited about working with partners in other regions of Asia. At this point, I don’t really have to preach about the importance of vision in a person’s life, and will just leave you with these words, by the American poet Sylvia Plath – “I shut my eyes and all the world drops dead; I lift my eyes and all is born again.”

The Vision Mission (TVM) is a Singapore-based non-profit organisation founded by Dr Jayant V Iyer, Dr Jason Lee and Mr Avinash Jayaraman, with the purpose of providing free eye care to those in need in Southeast and South Asia.